Five early-career pain researchers participated in the PRF-NAPS Correspondents program during the 2024 North American Pain School, which took place 23-28 June in Montebello, Québec City, Canada. The Correspondents program is a unique science communication training program that provides participants with knowledge and skills needed to communicate science effectively to a wide range of pain researchers, patients, and the greater public.

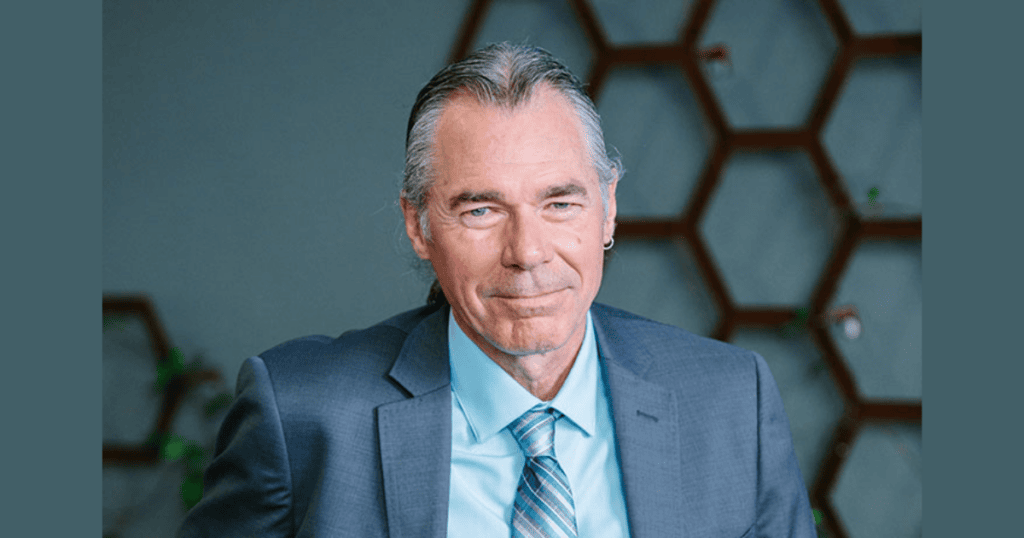

Michael “Mick” Sullivan – professor of psychology, medicine, and neurology at McGill University (Montreal, Quebec, Canada) – is an experienced researcher who has published more than 200 scientific articles in the fields of psychology and pain science. His current research seeks to address psychosocial risk factors for delayed recovery from pain-related disability. While speaking with PRF-NAPS Correspondent Morgan MacNeil, Mick discussed his career trajectory, his views on the future of psychological interventions in pain management, and his unique background as a folk musician.

Can you tell me about your background and how you became interested in the [pain] field?

During undergrad, I was working with someone who focused on stress-induced deaths in rodents. I had planned to do my PhD in epidemiology, but my honors thesis supervisor suggested, “Mick, why don’t you just do clinical psychology?” And I said, “I don’t want to do clinical psychology.” I was a big fan of numbers, and I thought that was the road I was going to take. In the end, my thesis supervisor convinced me to do clinical psych.

I applied and went to Concordia [University] for my graduate degree. I only got serious about psychology in the last year of my PhD. The rest of the time, I was just along for the ride, because I couldn’t say that anything thoroughly “grabbed me.” When I accidentally ended up at the rehab center on the pain ward, it just blew me away. I thought, There must be something we can do to help these people! Then, just from a curiosity perspective, I thought, Once you have a chronic pain condition, what allows some people to cope and others not so well?

I also became interested in how to go about changing clinical practice patterns. I realized that we’ve been doing things wrong at the initial stages of injury recovery, and we need to change that. The only way to do that is get on stage over and over again and basically let people know that there are other ways of doing things that are going to yield better outcomes than what they’re doing now.

Could you share some of the most significant challenges you have faced during your career and how you overcame them?

As a researcher, you need funding, and so funding is always a challenge. The funding agencies have several different mandates and various stakeholders that they must satisfy, so some of the decisions they’re making are based on scientific merit and sometimes based on political reasons.

Also, from a funding perspective, we realized early on that we needed to actually start testing interventions. We were learning enough about these psychosocial risk factors that we needed to start building some interventions that would specifically target them, but trying to get funds for a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in a psychosocial intervention has been almost next to impossible over the years. Until recently, the group that adjudicated the RCTs were pharmaceutical groups. They have the placebo control, everybody’s blind to everything, and it’s completely balanced. We can’t do that with a psychosocial intervention; we can’t have the perfect RCT. So it became frustrating to try to get some funding for that.

So would you say that one of the keys to overcoming those challenges is perseverance?

Yeah. And I think when you’re engaged to that degree in your research path, it’s going to take a lot to stop you. So for us, sometimes it means diverting our work to areas where research funding is more accessible. Thankfully, one of the things that became clear to a lot of injury insurers was that the psychosocial risk factors that we were studying were costing them a lot of money. So they’ve become open to funding research projects.

One of the common aspects of insurance systems is that they all have different criteria in place that will exclude claimants from a claim. There have been people who have felt they were treated unjustly in the insurance system forever, but when they would mention it, they were considered “complainers.” Once we started showing that individuals who scored high on a measure of perceived injustice following a work injury were costing insurers much more money, the insurers finally started to pay attention. All of a sudden, I was being invited to speak to their adjudicators and case managers on how they can make sure that their claimants weren’t experiencing this high level of perceived injustice.

How do you see the current trends in your area of expertise evolving over the next five to 10 years? What are the most exciting opportunities you see for future research in your field? What major gaps may have been closed and what gaps remain to be addressed?

The science of the psychology of pain was a lot easier when I started, because we didn’t know anything yet! It’s easier to find something important when we know very little. Today, as the questions have become more complex, I think we’ve realized that a lot of things that we thought were straightforward are a whole lot more complex than that. One of the things that was important to me in my quest to change clinical practice patterns was that, not only are psychosocial risk factors important, but we need to be assessing them when we’re working with pain patients.

I think we’ve made great gains in that regard in psychology – the Pain Catastrophizing Scale has been translated into 33 languages, and it’s probably used in every single pain clinic and rehabilitation center in the world. We have the tools, but the next question is: What do you do about it?

In primary care, assessment of catastrophizing is more likely to be used to blame the patient as opposed to help the patient, and I think that has led to some calls for a change in the terminology. I agree that we have a significant problem, but I argue that we don’t have a terminology problem: We have a community of practitioners that, in trying to protect their professional self-esteem, would prefer to blame the patient than to consider that this is a problem that they might not be able to do very much about.

I would say an area we haven’t attended [to] as much as we need is understanding the systemic influences on your topic of study as they exist in the world outside your lab. On the one hand, it’s the cloistered environment of the university that allows you to have more free-formed thought, but if your goal is real-world applications, you need to know more about the systems within which the problems that you’re studying exist.

Yesterday you gave a lecture on pain catastrophizing. What do you hope that the NAPS trainees took away from that?

One of the things that I was hoping to get people to reflect on is how some things you thought you had a good handle on at the beginning are not quite as they appeared, and you have to be open enough to recognize that, especially if some of the things run counter to certain theoretical models that you used to favor.

Also, to think in a very programmatic way about the research question that you’re asking, as opposed to just thinking of it as a one-off project. It’s like a lifelong road, where you’re going. Yeah, we’ve got the Pain Catastrophizing Scale in a lot of different places, but it took 30 years.

I tried to communicate the complexity of some of these psychosocial risk factors, because for most people, if they knew of catastrophizing, they knew of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale as having high and low scores. Now, I try to paint a bit more of a complete picture, highlighting the complexity of the social context within which these psychosocial risk factors exist as they take form and evolve.

How do you think multidisciplinary collaboration impacts the advancements in your research field and outcomes for patients with high pain catastrophizing?

From a research perspective, we need that multidisciplinary approach, because we have a very multifaceted problem, and sometimes it’s only people from other disciplines that will understand an aspect of the problem that we’re interested in – especially one that is not necessarily obvious from our lens.

From a practice perspective, I think we’ve overplayed “multidisciplinary” to a great degree. It’s very costly, and it’s relatively inaccessible. Early on in my career, while working at the rehab center, part of my job involved flying off to remote and rural communities in northern Ontario to assess people and make recommendations for treatment, with one major limitation: There were no resources in place to follow through on any of the recommendations that we made. One of the things about many rural and remote communities is that there are no psychologists there, so I started training anybody that seemed to be well suited for the task in the types of skills that could be useful in managing some of the challenging situations they face with their pain patients. Unexpectedly, a member of the regulatory body for psychologists came to me and said, “You can’t do that, because what’s indirectly happening is that training makes it very difficult for us to lobby for psychological resources in those communities, since you’re going to train people to do it.”

That got me thinking, Is it possible to take someone, early on in their career, and have them be a multi-skilled individual? Someone who’s got a bit of psych-, or physio-, or movement-related science education, and knows a bit more about the medicine side of things, but all in one person?

It would make that type of treatment much more accessible – it’s a lot easier to move one person around than to move a team around – and from a cost perspective, it would be so much more efficient. Now, we run a program called the Progressive Goal Attainment Program, where we train rehabilitation professionals in how to target psychosocial risk factors for delayed recovery following injury. Most of the people that we’ve trained are nurses, occupational therapists, kinesiologists, and vocational counselors.

If you were not working in academia or studying your current field, what would you be doing and why?

I realized over the years that even though I aspired to be a musician, it’s probably best I didn’t go down that road, because I’m okay as a musician, but I’m not good enough to make a good living at it, so that probably would not have been a good choice. Other than that, I would probably have gone down the epidemiology road.

You released an album called Common Ground in 1999. Have you released any country music since then? What got you interested in becoming a country music star?

The quick answer is no. There haven’t been any releases since then. But it was a wonderful experience; it was totally cool!

Here I am in Halifax in 1999, it’s a totally different genre of music compared to being in Montreal, and there was a buddy of mine, Steve Read; he was the caretaker of the ship behind the Acadia and also a musician. On Friday nights, everybody would converge onto the ship, and we’d just play and sing. Local recording artists there, and everybody was recording, so I thought, I [want to] record. I played in folky kinds of clubs for years; I paid my way through school playing in Irish bars, so I was used to performing – but performing to record is a totally different adventure.

Anyway, we go into CBC Studios, and the studio engineer says, “Mick, you know, you’re going about this all wrong. You can’t just bring your friends in to play on the CD. You need professionals, and someone who knows how to arrange and produce.” He goes, “It’s more complicated than you think.” I said, “Okay, so do you have any suggestions?” So he hooks us up with the bass guitarist for Nathalie MacMaster’s band, Bruce Jacobs. I remember I’d given him a tape of some of the stuff we had done so far.

Bruce meets me at my lab and he’s taking out all the sheet music, and goes, “You should see some of these ideas that I have for at least this piece.” And I’m looking at the sheets and looking at him, and he’s noticing that blank gaze, and he says, “Do you read?” I said, “I read. I just don’t read this.” He says, “Well, you’re [going to] have to learn how to read studio charts.” So I spent the next six months with Bruce Jacobs learning how to read studio charts. On the CD, it’s Natalie McMaster’s band. That is basically the studio band, and they were incredible. They made us sound 10 times better than we do sound. And then, when we got nominated for the award, that was over the top. I couldn’t believe that happened!

Bruce meets me at my lab and he’s taking out all the sheet music, and goes, “You should see some of these ideas that I have for at least this piece.” And I’m looking at the sheets and looking at him, and he’s noticing that blank gaze, and he says, “Do you read?” I said, “I read. I just don’t read this.” He says, “Well, you’re [going to] have to learn how to read studio charts.” So I spent the next six months with Bruce Jacobs learning how to read studio charts. On the CD, it’s Natalie McMaster’s band. That is basically the studio band, and they were incredible. They made us sound 10 times better than we do sound. And then, when we got nominated for the award, that was over the top. I couldn’t believe that happened!

Finally, can you please elaborate on a crucial piece of information that you shared with NAPSters on Sunday night when you stated that you participated in a production of Swan Lake? How did you land the role?

I’ve always had dogs and had a very significant interest in training them – I knew a lot of the dog trainers in Ottawa. There was this Italian ballet company that was doing Swan Lake at the National Arts Centre, and part of their production [was] that they wanted a hunter with two hunting dogs to be accompanying the king back from his hunting party. This dog trainer that I [knew called me and said], “Can I borrow Shannon?” – a yellow lab that I had at the time. And he goes, “It’s for something out at the National Arts Center; can you bring her there?” So I went down to the National Arts Center with Shannon, and he got his hunting dog. Then, the costume guy looks at him and goes, “No, no, no.” And he looks at me and goes, “Si, si.” And I became the hunter!

Morgan MacNeil is a PhD candidate in nursing at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. You can find her on X – @morganxmacneil.