As preclinical pain research increasingly includes both female and male animals, sex differences in pain are becoming more and more apparent. New work from Jeffrey Mogil, McGill University, Montreal, Canada, and Loren Martin, University of Toronto, Canada, now shows that male, but not female, mice developed context-dependent pain hypersensitivity following a pain conditioning experience. This suggests a fundamental difference in the processing and storage of pain information between the sexes, which the researchers link to stress. What’s more, the finding held up in people, likely demonstrating an evolutionarily conserved phenomenon.

“A definite strength of this study is that the main findings can be translated across species,” wrote Ruth Drdla-Schutting, a pain researcher at the Medical University of Vienna, Austria, in an email to PRF. Drdla-Schutting was not involved in the new research.

Speaking of Mogil and colleagues in an accompanying “Dispatch,” Theodore Price and Stephanie Shiers, University of Texas at Dallas, US, wrote: “Leading up to this work, Mogil and colleagues have been the torch runners for the study of sex differences in pain. Their groundbreaking research has revolutionized the pain field and changed the way pain researchers assess pain and pain plasticity. Based on their work, sexual dimorphisms in peripheral, spinal, and supraspinal pain circuitry have been identified, indicating that the acute and chronic pain state is complex with potentially vastly different underlying pathology in males and females.” The researchers “have now added an important new chapter to the phenomenon of pain memory.”

The study was published January 21, 2019, in Current Biology.

Memory test

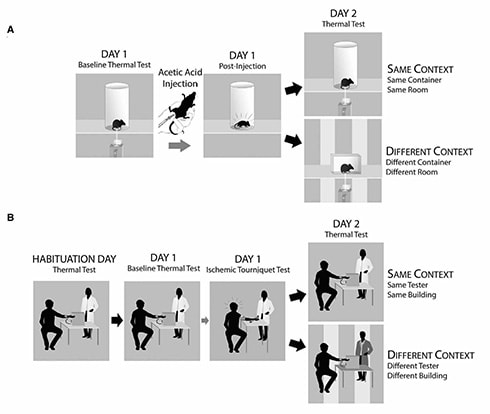

To test the effect of place conditioning on pain sensitivity, the researchers placed mice in a Plexiglas cylinder where they tested the animals’ paw withdrawal thresholds to radiant heat. Immediately afterward, the team injected the mice in the abdomen with acetic acid, which causes painful abdominal cramps and writhing behavior for 20 to 30 minutes, and then returned the mice to their home cages after 30 minutes. A day later, the mice were placed either back in the same cylinder in the same room, or in a novel cubicle in a different room, and again tested for heat pain sensitivity.

Remarkably, Mogil told PRF, “we found that only males tested back in the same room were more sensitive on day two than on day one. In every other group, we saw no change.”

The team then carried out a similar experiment in people. Forty-one male and 38 female subjects made continuous ratings of pain caused by a thermal probe to the inner forearm. After the testing was complete, the subjects underwent a much more painful experience: 20 minutes with a blood pressure cuff pumped up significantly higher than for a routine exam—while they exercised the arm. “It’s excruciating,” Martin said. “I’ve done it, and I’ll never do it again.” Mogil concurred.

The next day, subjects returned for a new round of thermal testing; this was to improve the accuracy of the study, the researchers told them. Half the subjects came back to the same room and underwent retesting by the same experimenter as the day before. But, for the other half of subjects, the investigators told them there had been a flood in the previous day’s testing room, and that the experimenter who tested them earlier had fallen ill, so these folks were retested in a different building by a different experimenter—a novel environment.

“For men, much like in mice, those tested in the same location showed a hypersensitive response when tested on the second day—they rated their pain as being a little bit more intense and unpleasant,” Martin said. Men tested in the novel environment and women tested in either environment had similar pain ratings as the day before. In neither people nor mice were there sex differences in pain ratings or thresholds on the first day.

Guys, why so sensitive?

To understand the roots of these sex differences in conditioned pain hypersensitivity, the researchers also asked subjects to fill out a series of questionnaires to gauge their mood and stress levels on both days of the experiment. “On the first day, stress ratings were quite variable, but there were no sex differences,” Mogil said. “On day two, almost everyone was relaxed.” Mogil hypothesizes that subjects were more at ease because they knew what would happen in the experiment (which this time included only thermal testing and not a repeat of the pressure cuff experience.)

But there was one striking exception: Men retested in the same environment reported significantly higher stress levels than the day before. And, “how stressed the men were predicted how much more sensitive they were to the pain, suggesting that stress caused the hypersensitivity itself,” Mogil said.

Stress was key to the phenomenon in male mice, too. The researchers used a drug called metyrapone to block the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the brain-body stress communication system, from making corticosterone. That prevented the hypersensitivity in males without affecting female pain behaviors. “If you block stress, you block the phenomenon,” Mogil said. Another indication that it depended on stress: Male mice in the same context environment had higher corticosterone levels than mice that did not develop hypersensitivity.

Testosterone seemed to be required, since castration abolished the conditioned pain hypersensitivity in male mice that developed it. Ovariectomy of female mice had no effect on pain threshold.

“Context-dependent stress-induced hyperalgesia is a well-described phenomenon. What is extremely surprising, though, is that this phenomenon was only observed in males,” Drdla-Schutting wrote to PRF.

Creating a pain memory

The researchers say that the pain hypersensitivity they observed in the males only is the manifestation of a “pain memory.” But it’s not necessarily a conscious memory.

“Pain memories are implicit,” Drdla-Schutting wrote. "They may be stored in the nervous system at a level precluding consciousness, [but that does not] prevent those pain memories from influencing the nervous system’s reaction to subsequent noxious events.”

In a final experiment in the mice, the team blocked pain hypersensitivity with an injection of zeta inhibitory peptide (ZIP). This peptide is an inhibitor of atypical protein kinase C (aPKC), a group of enzymes that play key roles in synaptic mechanisms underlying memory formation. ZIP injection prevented conditioned hypersensitivity when injected into the cerebrospinal fluid in cerebral ventricles—which was perhaps not surprising, considering the brain is the generally accepted locale for memory storage. But ZIP also blocked conditioned hypersensitivity when injected intrathecally into the spinal cord.

What does that say about where the pain memory is being formed and stored?

“That’s a hell of a question,” Mogil said. “To be honest, I’m pretty confused about how we can block it both in the brain and the spinal cord.” He once thought the spinal cord played a more simplistic role in pain processing, but these days, Mogil said, “I’m always astounded by just how much pain physiology is happening in the spinal cord. I’m starting to believe that, for whatever reason, it’s all about the spinal cord.”

Martin speculated that ZIP may have caused synaptic changes in the descending inhibition system, an idea also put forth in the Dispatch by Price and Shiers. Or, Mogil suggested, the physical pain memory itself may be encoded in the spinal cord, but brain activity underlies the emotional component of the memory. Martin plans to continue work to discern the underlying mechanisms and where in the nervous system they play out.

ZIP was initially thought to specifically block PKMzeta (PKMζ), a member of the aPKC family, but using it in experimental studies became somewhat controversial when investigators saw that it blocked multiple aPKCs. That discovery came about only after several years of research and many conclusions drawn about the peptide’s role in memory mechanisms (see PRF related news). Therefore, it’s not entirely clear whether the pain memory depends on PKMζ or another aPKC.

Drdla-Schutting said answering that question requires further study, but “given the similarities between learning and memory in the hippocampus and cortex and mechanisms underlying chronic pain development, PKMζ provides an attractive target for experimental pain research.”

“The implications of these findings are profound, as pain memories have been hypothesized to be critically involved in the chronification of pain,” Price and Shiers wrote.

An evolutionary perspective

Why would nature produce the newly identified sex difference in the first place?

One might expect that females, not males, would have developed sensitivity. According to the literature, Drdla-Schutting said, “women have a higher prevalence of developing chronic pain disorders, and stress-related pain disorders such as fibromyalgia or irritable bowel syndrome are more frequent in females.”

“After reading the paper,” she said, “I immediately asked myself, ‘What might be the reason for the absence of the conditioned pain hypersensitivity in females from an evolutionary perspective?’ ”

Mogil wondered why men but not women would experience stress. “One possibility is that although women have more sensitivity to pain, women have a lot more experience with pain—even at age 20,” so men may have been more stressed by the pain’s novelty. Another idea, he said, is that the phenomenon by which women have been said to forget the pain of childbirth is a more global mechanism. “Maybe women really do not remember pain as well as men.”

Looking back on evolution, males and females have experienced distinctly different types of pain. Women may begin experiencing regular monthly visceral pain in adolescence with their menstrual cycle, whereas males may have been more likely to be injured in an attack by a predator or violent adversary. “It may be more advantageous for a male to remember where they encountered physical pain if their survival depends on it, even if it’s unconsciously,” Martin said.

In contrast, Mogil said, “women’s pain happens wherever they are, so the environmental context doesn’t really matter too much.”

Considering all these possibilities, Drdla-Schutting wrote, “these questions are really exciting to me.”

A new model

A bonus element of the work is that the researchers developed a new animal model to test pain memories in rodents that translates to people—a tool in short supply for pain researchers.

Mogil said that sometimes researchers are studying pain mechanisms in animal models with uncertain relevance to human conditions. The new paradigm, he said, “is dead simple in both species. There is only one injection in the mice, so it’s more ethical than other paradigms that give multiple injections. And, importantly, if you can show that it works the same in mice and humans, and the sex differences also hold up, that gives you confidence to go and follow the mechanism” in future work.

“This study highlights that a patient’s personal history might actually contribute in a very specific way to chronic pain development,” Martin said. “That’s often something not taken into account.”

Stephani Sutherland, PhD, is a neuroscientist and freelance journalist in Southern California. Follow her on Twitter @SutherlandPhD.

Image credit: Ksenia Samorukova/123RF Stock Photo.