Editor’s note: The 17th IASP World Congress on Pain took place September 12-16, 2018, in Boston, US. At the Congress, 12 early-career pain researchers took part in the PRF Correspondents Program, a science communications training experience that provides participants with knowledge and skills needed to communicate science effectively to a wide range of pain researchers, and to patients and the wider public. As part of this program, the participants provided firsthand reporting from plenary sessions. Here, Perri Tutelman, a PhD student in clinical psychology, Dalhousie University & IWK Health Centre, Halifax, Canada, reports on a lecture delivered by plenary speaker Christopher Eccleston, University of Bath, UK. (For more on the upcoming 2020 IASP World Congress on Pain in Amsterdam, see here).

From the time we are children we are taught that humans have five senses: touch, sight, hearing, smell, and taste. What if we thought about pain in a similar way―as a physical sense that gives us information and guides our behavior? Only in this case there is one goal: to escape harm.

During the Ronald Melzack Award plenary lecture at the 2018 World Congress on Pain, Christopher Eccleston, University of Bath, UK, argued that considering pain from this vantage point is important for the insight it provides into the mechanisms of pain and how to tie discovery of mechanisms to treatment. And, as his lecture made clear, it also points the way toward a bright future for psychological therapies.

Pain: protecting against threat

Eccleston described pain as a component of the body’s protection system―as a sensation that warns of bodily threat and mobilizes action to return the body to a balanced state (a state of internal equilibrium or homeostasis). However, pain was not always viewed in this way. Early perspectives highlighted the neural anatomy of nociception―with pain being the direct result of peripheral nociceptor activation, and that alone.

However, over the past several decades, it has become clear that nociception and pain are not the same thing. It is now thought that pain is a complex sensation resulting from the brain’s interpretation of a nociceptive signal as a sign of potential bodily threat. From this perspective, the experience of pain is determined by a myriad of biological, psychological, and social factors that vary from person to person. This highlights the integrated nature of the body and psychology, and emphasizes the importance of considering both in pain interventions.

Three levels of protection

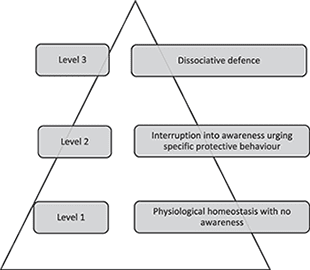

Eccleston proposed a three-tiered framework that describes the role of pain in bodily protection and groups different types of pain according to their mechanisms (termed the “Tripartite System of Threat Protection”). According to Eccleston, the overall function of pain is to protect the body from threat while causing the least disruption to one’s physical and cognitive functioning as possible. However, pain can be interrupting to varying degrees. Consider the impact of pain caused by a paper cut versus the impact of chronic musculoskeletal pain. While pain from a paper cut may interfere mildly with function for a relatively short period of time, chronic pain is almost always within one’s conscious awareness and often leads to frequent and severe interruption. Other factors, such as how dangerous an individual perceives the pain to be, and how anxious a person is about bodily sensations in general, can also influence the degree to which pain interferes.

Eccleston said that current interventions for pain act at different levels of the tripartite system. Level 1 refers to a minimal state of pain interruption. Here, physiological changes take place within the body to protect it from potential harm and return it to a balanced state. This occurs automatically, without pain ever coming into conscious awareness. Eccleston said that pharmacological interventions such as pain medications, and some psychological interventions like relaxation, meditation, and education about pain, all act at this tier of the system to prevent pain from entering conscious awareness, ensuring the pain causes as little disruption as possible.

Level 2 of the tripartite system describes a state in which an individual becomes aware of and is interrupted by pain. This happens when the body’s protection efforts at level 1 are not effective, and conscious awareness is necessary to take action to ensure safety and restore equilibrium. According to Eccleston, most of our current psychological interventions for pain, which have focused on altering individuals’ attention to pain, as well as their thoughts and feelings about pain, act at this level of protection.

Regarding those interventions, “it is an exciting time to be a pain psychologist,” said Eccleston, “We have amazing interventions for psychological treatment of pain currently.”

Indeed, while attention modification interventions, such as distraction and sensory monitoring, have had disappointing results for the treatment of chronic pain, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has yielded impressive effects. CBT is a short-term, skills-based form of talk therapy that focuses on changing maladaptive thoughts, feelings, and behaviors related to pain, and results in small but significant improvements in pain, depression, disability, and anxiety in both adults and children with chronic pain. An updated review of 67 trials using CBT for chronic pain treatment will be published later this year, Eccleston said. Additional psychological treatments for chronic pain, such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), are gaining popularity. However, Eccleston cautioned that evidence for their clinical effectiveness is still emerging.

A relatively unexplored area of psychological treatment for chronic pain at level 2 is “identity therapies,” Eccleston noted. Not only does the interruptive function of chronic pain have an impact on a person’s day-to-day functioning, but also on one’s identity and sense of self. Identity therapies, such as narrative therapy and emotion- and compassion-based therapies, focus on the construction of more adaptive ways of viewing oneself, one’s experiences and feelings, and one’s relationships with others. These therapeutic modalities are routinely used in the treatment of mental health disorders, such as trauma-related disorders, and warrant investigation for chronic pain, according to Eccleston.

Finally, level 3 of the tripartite system is the last stage of protection, which Eccleston described as “a dissociative departure to protect the self.” He said that individuals will enter a dissociative state when they cannot or choose not to escape from the threatening sensation of pain that emerges into conscious awareness at the second level of the system. He suggested that dissociative departure in response to sensations such as pain can take various forms such as feelings of lost awareness of one’s surroundings, out-of-body or unreal experiences, and physical sensations such as paresthesia. In the pain field, the most common example of dissociative departure is the phenomenon of phantom limb pain, in which a person feels pain in a body part that is no longer present.

However, Eccleston argued that dissociative defense is likely far more common in individuals with both acute and chronic pain than what has been described in the literature to date, and is an area that requires additional study. Further, he suggested that “radical interventions” that harness the power of controlled dissociation are on “the cusp of modern psychoanalgesics” (psychological interventions that cause analgesia). This class of interventions, such as hypnosis, virtual reality immersion, and structured illusions, represent a critical convergence of the mind and the body. According to Eccleston, these interventions hold significant promise for the treatment of pain, but our understanding of their mechanisms and efficacy are in their infancy.

Looking ahead, Eccleston said that the next generation of psychological pain interventions, in order to be successful, must be the result of collaborative, multidisciplinary efforts that consider the mechanism and function of pain, and that bridge the body and psychology. That is, he said that psychologists can no longer think of the body as simply a “taxi for the mind,” and medical professionals can no longer think of the mind as simply an add-on to the body. Psychological interventions for chronic pain will only move forward with use of innovative methods to integrate both the body and psychology, especially interventions that map onto level 3 of the tripartite system.

“If you remember nothing else from this presentation,” Eccleston said, “we need to put the body back into psychology, and we need to put psychology back into medicine.”

Perri Tutelman is a PhD student in clinical psychology, Dalhousie University & IWK Health Centre, Halifax, Canada.

Image credit: Christopher Eccleston, 2019.

Additional reading

Chronic pain as embodied defence: implications for current and future psychological treatments.

Eccleston C

Pain. 2018 Sep; 159 Suppl 1:S17-S23.

Embodied pain-negotiating the boundaries of possible action.

Tabor A, Keogh E, Eccleston C

Pain. 2017 Jun; 158(6):1007-1011.

Eccleston C. Embodied: The psychology of physical sensation. Oxford University Press, 2015.